I am occasionally asked an impossible question which I inevitably fail to answer.

The question is: “What is your favorite Jane Austen novel?”

As returning viewers and readers will know, I adore Austen. I adore all of her writings, I’ve reread them many times, and the lessons that I have learned from Jane are deeply ingrained in my character and personality.

Yet, I never have an answer to give to the question.

I think perhaps I don’t even understand the question. I find great books, generally, to be so multi-faceted that they all tend to elude my ability to precisely rank and rate them, but I am totally unable to make the attempt with Austen’s novels in particular. I think each of her works are so charming and meaningful that it’s unthinkable to set one apart as the finest, or to choose one as the best and one as the worst.

Jane’s stories may follow slightly different patterns, but they’re all cut from the same exquisite and exceptional material, all sewn together with the same masterful and meticulous hand. But while I can’t pit them one against the other or choose a favorite, I can identify one particular quotation which, for me, encapsulates the underlying bedrock that gives power to all of her novels, the thing that makes me love them so much, the reason I find them to be so captivating and inspiring, the most essential element of her work.

There are so many delightful things about Austen’s novels - the language, the setting, the insight into human nature, the romance, the humor - and it’s perhaps one of the hallmarks of her skill that different readers can find almost opposite meanings in her books and love her for completely different and even divergent reasons.

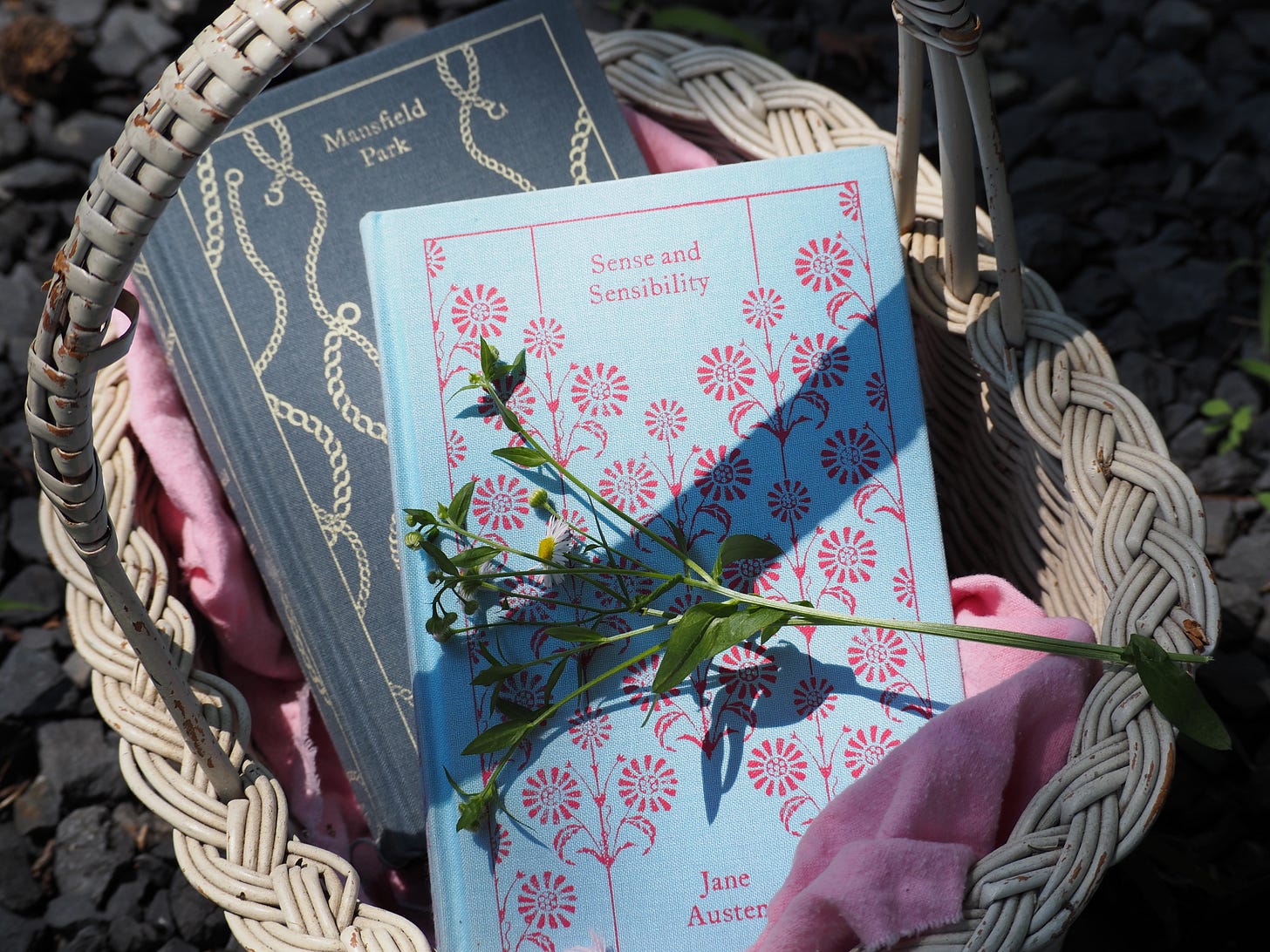

But for me, this is it. This is the element that gives beauty and strength to every other beautiful and strong element in her writing. The quotation is short, and it’s spoken by the one and only Fanny Price of Mansfield Park:

“We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be.”

Fanny is not alone in this conviction. Each of Austen’s main heroes and heroines are engaged in the important, painful, and difficult work of attending to that better guide within themselves: it is both how and why they grow. Throughout the course of each novel, the protagonists discover some unpleasant shortcoming in their own habits and characters; they learn something about themselves that they didn’t want to know - and then they proceed to do something about it. Built into Austen’s novels is this idea that while we can’t change others - and we shouldn’t hold our breath waiting for them to change - we can change ourselves, but it’s going to be unpleasant. It’s going to take patient effort, endurance of discomfort, and a large dose of both humility and unselfishness, but it’s work that’s vital to our soul and ultimate well-being.

The willingness of Austen’s protagonists to open their reason to understanding and open their eyes to look their problems in the face is what differentiates them from other characters in the novels, particularly from the less savory characters. While Fanny Price’s line illustrates the principle of attending to that better guide, there’s another quotation in the same novel in which another character, Maria Bertram, illustrates the principle of purposefully ignoring that better guide. In this passage, Maria is hoping something will delay the return of her father - because when he returns she will have to face up to the choices she’s made.

“It was a gloomy prospect, and all she could do was to throw a mist over it, and hope when the mist cleared away she should see something else….there were generally delays, a bad passage or something; that favouring something which everybody who shuts their eyes while they look, or their understandings while they reason, feels the comfort of.”

We’re all human, we’re all flawed and frail and mortal. We all get lost in inner mists at times. But there’s a big difference between striving to dispel the fog and seeking to increase it or choosing to linger in it.

I mentioned in my last reading wrap-up that classics often seem to pick up on this theme of the inner fogs that we throw over our own problems, but different classics take different approaches to the idea. I read Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited last month, and while there were thought-provoking observations and beautiful descriptions to enjoy, I felt that Waugh was almost unhealthily obsessed with the inner fogs his characters cultivated. I found myself wondering early on what one of the characters could have done differently to have held her family together better, but then I realized that this was the Jane Austen training in me, and it was not at all a question Waugh was interested in. The ending of Brideshead, which I had expected to be the most powerful part, fell very, very flat for me, and I think this is why.

Evelyn Waugh plays with the idea that every human being is hooked by God on a line long enough to allow them to wander the world but be pulled back with a twitch upon the thread. And in fact, it’s true that God’s love for each and every human on earth is beyond what our human minds can comprehend. God’s mercy can reach into the tiniest crack. It’s good to remind ourselves of this when we’re tempted to judge others, because we don’t know how God’s grace may be working in their lives.

**Minor SPOILER WARNING: there are some observations ahead which could be considered spoilers for Brideshead Revisited, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and Mansfield Park.**

But when we take this idea of wandering the world, waiting for a twitch on the thread, and turn it around and apply it to ourselves, it becomes incredibly dangerous. While we wander, wherever we wander, at every moment, God is constantly pulling us towards Him, actively inviting us into His grace. It may be through methods we don’t understand and don’t like, but He’s always calling to us out of His great love for us. Many of the Brideshead Revisited characters seem to resist God’s love and grace for almost their whole lives. Time and time again they turn away from the pull. Here’s how Waugh describes this through his narrator:

"How often, it seemed to me, I was brought up short, like a horse in full stride suddenly refusing an obstacle, backing from the spurs, too shy even to put his nose at it and look at the thing.”

But a consideration that Waugh doesn’t seem to explore is the idea that, in so refusing the obstacle and refusing to look, the characters are numbing themselves. They’re creating a habit of resisting God’s grace and allowing themselves to indulge that habit over and over again.

Habits are the tiny continual choices we make that become not only who we are but who we choose to be. God’s strength is endless, but ours isn’t, and free will is a reality. If you allow yourself to refuse a jump again and again, why would you expect to react any differently when confronted by the jump at the last minute, when all the years that could have been spent slowly, painfully, ineptly, but still consciously striving to build up and cultivate the skill and strength to meet that jump have instead been spent in stubbornness and selfishness?

This character type is common in Austen’s novels: it’s what most of her antagonists have in common. Austen’s villains are compelling because they’re multi-dimensional. Often they have very good qualities, but the selfish habits that they’ve indulged in sabotage the opportunities of happiness that come their way. Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park is one example; Willoughby in Sense and Sensibility is another. Both of them end up abandoning the women they “rationally as well as passionately loved” because they allow their selfish habits to control their actions rather than their better judgments. Here’s how Elinor (and by extension, Austen) sums up Willoughby:

“His whole conduct declared that self-denial is a word hardly understood by him…The whole of his behavior, from the beginning to the end of the affair, has been grounded on selfishness. It was selfishness which first made him sport with your affections, which afterwards, when his own were engaged, made him delay the confession of it, and which finally carried him from Barton. His own enjoyment, or his own ease, was, in every particular, his guiding rule.”

And as mentioned earlier, the fascinating thing in Jane Austen is that characters can change their habits; but the villains don’t, while the heroes do. The famous Fitzwilliam Darcy, for example, was similarly encumbered with “a selfish disdain for the feelings of others.” He “was given good principles but left to follow them in pride and conceit.” But when Elizabeth calls him out, he takes it to heart, although admittedly not right away - it takes time. Within a reasonable interval, he rises to the challenge of true self-reflection and tries to make changes for the better - not just to win Elizabeth back but for the sake of his own character. I think the thing about Darcy that many people miss, the true reason he’s incredible, is this: he manages to prove that his character is even more impressive than his admittedly-impressive estate.

To phrase it another way, for each of these men (Darcy, Crawford, and Willoughby), knowing an Austen heroine (Elizabeth, Fanny, and Marianne) was an operation of God’s grace, a twitch of the thread, a call to attend more closely to their “better guide within themselves.” It’s no coincidence that that line from Fanny is literally spoken by her to Henry Crawford. In that scene, he’s asking Fanny to tell him what to do, but, as Fanny points out, no one else can tell us what to do. We each have to learn to listen to the voice of conscience within ourselves. Where Darcy responds to that inner voice, Willoughby and Crawford resist it and reject it and pay the price, living lives of dissatisfaction, or as Jane puts it: “providing for [themselves] no small portion of vexation and regret: vexation that must rise sometimes to self-reproach, and regret to wretchedness.”

This isn’t one-sided: the women in Jane Austen are also called by grace to see themselves as they really are and make changes for the better. The female protagonists respond and cooperate with this call, the female antagonists do not. Elizabeth learns to look beneath surface impressions, to see how her judgment can be clouded by her own pride and prejudice. Fanny learns to come out of her shell, to assert herself when necessary, and to be a rock of strength and encouragement for those around her. Marianne learns that she’s let her indulgence of her emotional sensibilities and her anxiety for a soulmate blind her to reality and neglect her duty not just to other people in her life but to God. Out of the three heroines, Marianne has the most to learn, and her transformation is the most powerful and the most powerfully expressed:

“I considered the past; I saw in my own behavior since the beginning of our acquaintance with him last autumn, nothing but a series of imprudence towards myself and want of kindness to others. I saw that my own feelings had prepared my sufferings, and that my want of fortitude under them had almost led me to the grave…I did not know my danger till the danger was removed; but with such feelings as these reflections gave me, I wonder at my recovery - wonder that the very eagerness of my desire to live, to have time for atonement to my God, and to you all, did not kill me at once.”

This passage is one of the few times in Jane Austen in which the characters explicitly mention their faith: Marianne talks about having “time for atonement to my God.” But maybe faith has in fact been in the novels the whole time, because what could the “better guide within ourselves” be other than God himself? The process of facing your problems and trying to improve your character is nothing more or less than responding to and cooperating with God’s grace and love and mercy. This is why I think Jane Austen’s faith, although to some not obvious, actually saturates every bit of her novels; you can’t take it out without taking out the most essential and powerful element of her work.

The romance element of Jane Austen’s novels is often the theme that gets emphasized, but Austen is only using romantic relationships as a vehicle to exemplify one of the powerful ways God calls us to open our eyes to attend to our better guide, to allow it to show us who we really are and what we need to do to become more than what we presently are.

The characters of real flesh and blood human beings are perhaps not so easily sorted into the clear-cut categories of Darcy vs. Willoughby or Marianne Dashwood vs. Maria Bertram, and God is certainly calling to the Willoughbys and Maria Bertrams of the world just as powerfully as He is calling to the Darcys and Mariannes. We all struggle to attend to our better guides, so we should never pretend to know what another person’s guide might be saying.

But I think Jane Austen’s incisive insight into the workings of the heart and soul are what make her works so timeless; they’re as true today as they were two hundred years ago. Her lessons certainly help me to better understand myself and others and inspire me to try to attend always to my better guide, clear away my inner fogs, cooperate with God’s sometimes difficult grace, and put in the painful practice to be able to face the obstacles that may pop up in my way.

As I review Austen’s seven finished works (let’s not leave out Lady Susan, it’s amazing), I see this vital principle articulated so brilliantly in each of them - and I’m sure it would have been just as present if she had lived to finish more novels - so that if there were more than seven, I would probably be equally unable to rank them or to choose a favorite. 😆

I could continue on about how this theme plays out in Austen’s others characters, but this piece already seems lengthy enough! It’s always fun to read different impressions of Austen, and these are the reflections that have been popping into my head this month. What are your favorite lessons learned from Jane? Let me know in the comments below!

The quote you share from Fanny Price here is one of my absolute favorites from Austen! I know some readers find Fanny difficult to like because they find her strong moral convictions and her commitment to them "priggish," but I admire her character for these very same reasons.

The lesson I most return to from Jane Austen, though, comes from Pride and Prejudice, when Darcy excuses the poor impression he made on the people of Hertfordshire on his lack of social ease. Elizabeth's response is something I always keep in mind when I'm facing something I find difficult: "My fingers do not move over this instrument in the masterly manner which I see so many women's do . . . but then I have always supposed it to be my own fault--because I would not take the trouble of practising." I think this exchange also reflects the themes of change and growth you analyze so well here, as Elizabeth points out that we all have it within our power to do better--if only we commit to the necessary work!